Mark Strauss

Recently declassified documents reveal new details about Project AZORIAN: a brazen, $800-million CIA initiative to covertly salvage a Soviet nuclear submarine in plain sight of the entire world.

The story begins in March 1968, when a Soviet Golf II submarine — carrying nuclear ballistic missiles tipped with four-megaton warheads and a seventy-person crew — suffered an internal explosion while on a routine patrol mission and sank in the Pacific Ocean, some 1,900 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii. The Soviets undertook a massive, two-month search, but never found the wreckage. However, the unusual Soviet naval activity prompted the U.S. to begin its own search for the sunken vessel, which was found in August 1968.

The submarine, if recovered, would be a treasure trove for the intelligence community. Not only could U.S. officials examine the design of Soviet nuclear warheads, they could obtain cryptographic equipment that would allow them to decipher Soviet naval codes. And so began Project AZORIAN. The U.S. intelligence community commissioned Howard Hughes to construct a massive vessel — dubbed the Hughes Glomar Explorer (HGE) — to recover the sub. The ensuing salvage operation, which began in 1974, was only a partial success; the U.S. was planning to embark on a second attempt when, in 1975, the story was leaked to the press, and the operation was canceled.

In the years that followed, it was notoriously difficult to get information on Project AZORIAN beyond the details that were published in the newspapers. In response to a FOIA request, the CIA refused to release any documents, saying that it could “neither confirm or deny” any connection with the Hughes Glomar Explorer. (As a result, the phrase “neither confirm or deny” became popularly known as the “glomar response” or “glomarization.”)

In 2010, the CIA permitted the publication of a heavily redacted, 50-page article describing Project AZORIAN that had appeared in a fall 1978 issue of the agency’s in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence. And, in recent years, veterans of the operation have come forth to tell their stories.

Now, however, we have even more details, thanks to the publication of the latest volume of The Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS). Compiled by State Department historians, the FRUS series is an invaluable resource, containing declassified documents that include diplomatic cables, candid internal memos and minutes of meetings between the president and his closest advisors. For anyone who has the stamina to read through these 1,000-plus page volumes, it’s a unique opportunity to experience history as it happened.

The most recent FRUS, National Security Policy: 1973-1976, contains some 200 pages on Project AZORIAN. And it doesn’t disappoint.

We’re Gonna Need A Bigger Boat

In 1969, the CIA assembled a small task force of engineers and technicians to come up with a concept for recovering the submarine. The technological and logistical obstacles were considerable. How could the U.S. salvage a 2,500-ton submarine, sitting on the ocean floor, at a depth of 16,500 feet? And, how could the U.S. conduct such a large-scale operation without arousing suspicion or being detected by Soviet reconnaissance?

Ultimately, the engineers opted for a plan that sounded like it was lifted from the plot of a James Bond film (actually, it did become the plot of a James Bond film). The plan involved three vessels: 1) An enormous recovery ship with an internal chamber and fitted with a bottom that could open and close. This ship would use a docking leg system that would, in effect, turn it into a stable platform for using a lifting pipe to raise and lower a 2)”capture vehicle” fitted with a grabbing mechanism that would be designed to align with the hull of the sub. The capture vehicle would be secretly assembled on a 3) massive barge with a retractable roof. The barge would be submersible, so that it could slip beneath the ocean, under the recovery ship, open its roof and deliver the capture vehicle — all the while remaining hidden from any potential reconnaissance.

The CIA contracted the Summa Corporation — a subsidiary of the Hughes Tool Company owned by billionaire industrialist Howard Hughes — to build the 618-foot-long, 36,000-ton recovery vessel, which was dubbed the Hughes Glomar Explorer (HGE).

Expand

Expand

Of course, the sight of a floating behemoth lingering in the Pacific Ocean was bound to raise some eyebrows. So, Project AZORIAN concocted a cover story that the HGE was being built for Hughes’s private commercial venture to mine manganese nodules located on the ocean floor. A May 1974 memo to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger explained:

The determination reached was that deep ocean mining would be particularly suitable. The industry was in its infancy, potentially quite profitable, with no one apparently committed to a hardware development phase and thereby possessing a yardstick by which credibility could be measured… Mr. Howard Hughes… is recognized as a pioneering entrepreneur with a wide variety of business interests; he has the necessary financial resources; he habitually operates in secrecy; and, his personal eccentricities are such that news media reporting and speculation about his activities frequently range from the truth to utter fiction.

And they were right. Much of the media unknowingly and enthusiastically popularized the story. “The race is on to exploit mineral riches that lie in the deep,” declared the Economist magazine. New Scientist reported on the HGE‘s capacity to “suck up” 5,000 tons of ore per day.

But as Project AZORIAN progressed, government officials began to express doubt as to whether it was still worth going through with the mission. A number of years had passed since the sub sank. Was it an intelligence asset or an artifact?

An ad hoc committee took another look at the matter and decided, on measure, that there was still much to be gained from the operation. Although the sub’s short range SS-N-5 missiles were no longer deemed a major threat, they could still “provide potentially important technologies” relevant to the Soviet Union’s recently deployed, long range SS-N-8 missiles. And the cryptographic equipment “would be of very high value to the U.S. intelligence effort against Soviet naval forces.”

Moreover, in a separate memo, the Director of Central Intelligence expressed his view that the only thing more worrisome than pissing off the Soviet Union would be pissing off private contractors:

I think we should be concerned about the Government’s reputation. To the contractors, a termination decision at this late date would, I believe, seem capricious. This is a serious matter in intelligence programs where security and cover problems require a closer relationship between the Government and its contractors than is customary in other contractual areas. Our reputation for stability within the contractor community is therefore an important matter, and I am concerned that in the wake of such a termination it would become more difficult to find corporations willing to participate with us in such a cooperative way.

It should be noted that, in addition to retrieving equipment from the sub, a memo stated that “provisions for handling and disposition of the target crew remains are generally in accordance with the 1949 Geneva Convention. They will be handled with due respect and returned to the ocean bottom.” A later memo revealed the intent to collect the deceased crew’s personal effects for potential return to their families — a goodwill gesture to help ease tensions in the event that the Soviets discovered the true intent of the operation.

Finally, on June 3rd, 1974, a memorandum from the National Security Council to Kissinger announced:

Culminating six years of effort, the AZORIAN Project is ready to attempt to recover a Soviet ballistic missile submarine from 16,500 feet of water in the Pacific.

The recovery ship would depart the west coast 15 June and arrive at the target site 29 June. Recovery operations will take 21–42 days (30 June to 20 July–10 August).

Project managers estimated a more than 40% chance of success — an acceptable figure, since the estimates for high-risk, innovative endeavors seldom went higher than 50%.

Two days later, the operation was approved.

AZORIAN Springs a Leak

The recovery mission, which lasted from June to August 1974, was only partially successful. Although a portion of the submarine was retrieved, the remainder of the vessel fell away from the capture vehicle following a failure of the grabber mechanism.

The deputy secretary of defense briefed Kissinger:

Extensive analyses of the grabber failures have resulted in conclusions that new grabbers must be fabricated that incorporate a less brittle material and improved design techniques. All necessary actions are now being taken to reconfigure the capture vehicle and refurbish the recovery ship for a second mission during the next optimum weather period; i.e., July and August 1975.

Should the U.S. attempt a second mission? Things had changed a lot in Washington since the Hughes Glomar Explorer set out to sea. President Richard Nixon had resigned on August 9th, and White House officials had entered into full-scale, cover-your-ass mode. There were growing doubts, given the current atmosphere in Washington, whether the CIA could sustain the operation for another year without the story leaking to the press.

Still, the consensus favored continuing the initiative. However, even Henry Kissinger, who was among the operation’s strongest proponents, began to have private doubts. After one meeting with intelligence and defense officials in January 1975, Kissinger had a candid conversation with President Gerald Ford:

Kissinger: “There are so many people who have to be briefed on covert operations, it is bound to leak. There is no one with guts left. All of yesterday they were making a record to protect themselves about AZORIAN. It was a discouraging meeting. I wonder if we shouldn’t get the leadership in and discuss it. Maybe there should be a Joint Committee.”

Ford: “I have always fought that, but maybe we have to. It would have to be a tight group, not a big broad one.”

Kissinger: “I am really worried. We are paralyzed.”

Kissinger had another reason to be worried. Since as early as January 1974, New York Times journalist Seymour Hersh had been investigating the story. William Colby, the Director of Central Intelligence had twice met with Hersh — on February 1st, 1974 and February 10th, 1975 — urging him to delay publication. But how much longer could the story be kept out of the media?

Less than a week, as it turned out, though it wasn’t Hersh who broke the story. Project AZORIAN became public knowledge because of a burglary that had taken place on June 5th, 1974 (ironically, the exact same day that the operation had been approved).

The Los Angeles headquarters of the Hughes-owned Summa Corporation had been broken into. The burglars made off with cash and four boxes of documents. An inventory of papers that were missing after the burglary included a memo describing the secret CIA project. Had the memo been stolen, or had it been destroyed prior to the break-in? Nobody knew for sure.

Months later, the LA police reported that they had been contacted by an intermediary for an individual who claimed to be in possession of the stolen papers, though he did not specifically mention any memo concerning the CIA and Project AZORIAN. The price for returning the papers would be $500,000.

What happened next can be best described as a comedy of errors. The CIA informed the FBI of the LA police report and the fact that the papers being offered for sale might include a sensitive memo dealing with Project AZORIAN. The FBI then told the LA police about the memo; and the LA police told the intermediary. By trying to determine whether the extortionists actually had the memo, the CIA itself had set into motion the circumstances that culminated in a leak.

On February 7th, 1975, the Los Angeles Times published a brief article, “U.S. Reported After Russ Sub,” saying that, according to “reports circulating among local law enforcement officers,” Howard Hughes had contracted with the CIA to “raise a sunken Russian nuclear submarine from the Atlantic Ocean… The operation, one investigator theorized, was carried out — or at least attempted — by the crew of a marine mining vessel owned by Hughes Summa Corp.”

Expand

Expand

It was a vaguely sourced article, containing errors, but the story was out. On March 18th, 1975, syndicated columnist Jack Anderson mentioned the Hughes Glomar Explorer on his national radio show, and declared his intention to reveal more details about the operation. As a result of that announcement, journalists, including Hersh, were no longer obliged to delay publication. The next day, several major newspapers — including the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and The New York Times — published front-page stories revealing that the Hughes Glomar Explorer, in an operation led by the CIA, had recovered a portion of a sunken Soviet submarine during the summer of 1974.

Mission Impossible

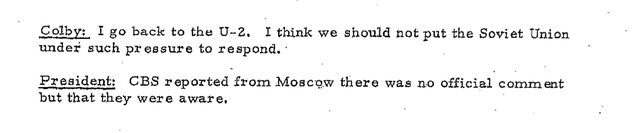

To the surprise of the White House, the Soviet reaction was muted. There had been expectations of outrage similar to the 1960 U-2 incident, when an American spy plane had been shot down over the airspace of the USSR.

Expand

Expand

A report prepared by the CIA in April 1975 believed that the Soviet decision to refrain from a public response was due to several factors:

— It precludes embarrassment at home and abroad in having to admit for the first time the loss in 1968 of the Golf submarine.

—It avoids public acknowledgement of Soviet inability to locate the lost submarine vis-a-vis the obviously superior technical capabilities of the U.S. to not only locate but recover their submarine.

— It hides chagrin at the failure of Soviet intelligence services being unable to uncover the true purpose of the Hughes deep ocean mining project during its five-year development.

The CIA concluded that the Soviet Union had a vested interest in not publicizing the affair any further. However, the CIA also warned, “It seems beyond doubt that the Soviets would go to great lengths to frustrate or disrupt a second mission.”

That left one remaining question: How would the Soviet Union actually respond if a second recovery mission were attempted? The White House had not acknowledged any official connection to the Hughes Glomar Explorer. Would the Soviet navy actually open fire on an ostensible U.S. civilian vessel?

That turned out to be a moot question. Additional analysis from the CIA revealed multiple ways that the Soviets could covertly — and rather easily — disrupt the carefully choreographed operation. It would just require a couple of divers with cables to muck up the equipment.

On June 16th, 1975, Kissinger sent a memorandum to President Ford:

It is now clear that the Soviets have no intention of allowing us to conduct a second mission without interference. A Soviet ocean-going tug has been on station at the target site since 28 March, and there is every indication that the Soviets intend to maintain a watch there. Our recovery system is vulnerable to damage and incapacitation by the most innocent and frequent occurrences at sea—another boat coming too close or “inadvertently” bumping our ship. The threat of a more aggressive and hostile reaction would also be present, including a direct confrontation with Soviet navy vessels.

And with that, Project AZORIAN was terminated. The total cost of the operation: $800 million, which, in current dollars, translates into more than $3 billion. The Hughes Glomar Explorer would eventually be refitted to match its cover story and perform deep-sea drilling. It was sold to a private company in 2010 for $15 million.